The first ever exoplanets were discovered 30 years ago around a rapidly rotating star, called a pulsar. Now, astronomers have revealed that these planets may be incredibly rare. The new work will be presented tomorrow (Tuesday 12 July) at the National Astronomy Meeting (NAM 2022) by Iuliana Nițu, a PhD student at the University of Manchester.

The processes that cause planets to form, and survive, around pulsars are currently unknown. A survey of 800 pulsars followed by the Jodrell Bank Observatory over the last 50 years has revealed that this first detected exoplanet system may be extraordinarily uncommon: less than 0.5% of all known pulsars could host Earth-mass planets.

Pulsars are a type of neutron star, the densest stars in the universe, born during powerful explosions at the end of a typical star’s life. They are exceptionally stable, rapidly rotating, and have incredibly strong magnetic fields. Pulsars emit beams of bright radio emission from their magnetic poles that appear to pulse as the star rotates.

“[Pulsars] produce signals which sweep the Earth every time they rotate, similarly to a cosmic lighthouse,” says Nițu. “These signals can then be picked up by radio telescopes and turned into a lot of amazing science.”

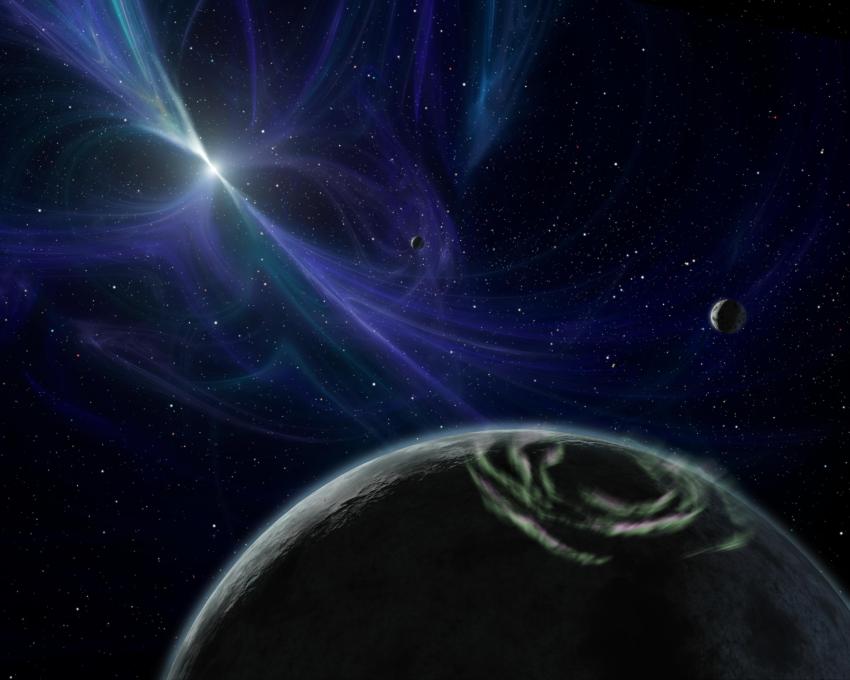

In 1992, the first ever exoplanets were discovered orbiting a pulsar called PSR B1257+12. The planetary system is now known to host at least three planets similar in mass to the rocky planets in our Solar System. Since then, a handful of pulsars have been found to host planets. However, the extremely violent conditions surrounding the births and lives of pulsars make ‘normal’ planet formation unlikely, and many of these detected planets are exotic objects (such as planets made mostly of diamond) unlike those we know in our Solar System.

A team of astronomers at the University of Manchester performed the largest search for planets orbiting pulsars to date. In particular, the team looked for signals that indicate the presence of planetary companions with masses up to 100 times that of the Earth, and orbital time periods between 20 days and 17 years. Of the 10 potential detections, the most promising is the system PSR J2007+3120 with the possibility of hosting at least two planets, with masses a few times bigger than the Earth, and orbital periods of 1.9 and ~3.6 years.

The results of the work indicate no bias for particular planet masses or orbital periods in pulsar systems. However, the results do yield information of the shape of these planets’ orbits: in contrast to the near-circular orbits found in our Solar System, these planets would orbit their stars on highly elliptical paths. This indicates that the formation process for pulsar-planet systems is vastly different than traditional star-planet systems.

Discussing the motivation of her research, Nițu says: “Pulsars are incredibly interesting and exotic objects. Exactly 30 years ago, the first extra-solar planets were discovered around a pulsar, but we are yet to understand how these planets can form and survive in such extreme conditions. Finding out how common these are, and what they look like is a crucial step towards this.”

Media contacts

Dr Robert Massey

Royal Astronomical Society

Tel: +44 (0)20 7292 3979

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877 699

nam-press@ras.ac.uk

Ms Gurjeet Kahlon

Royal Astronomical Society

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877700

nam-press@ras.ac.uk

Ms Cait Cullen

Royal Astronomical Society

nam-press@ras.ac.uk

Science contacts

Iuliana Nițu

University of Manchester

iuliana-camelia.nitu@manchester.ac.uk

Dr Michael Keith

Department of Physics and Astronomy

University of Manchester

michael.keith@manchester.ac.uk

Further information

This work is to be presented at the 2022 National Astronomy Meeting on Monday 11 July.

Image link: https://nam2022.org/images/artist_impression.jpeg

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Caption: Artist impression of the pulsar-planet system PSR B1257+12 detected in 1992. The pulsar and three radiation-doused planets are all that remains of a dead star system.

Notes for editors

About NAM 2022

The NAM 2022 conference is principally sponsored by the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS), the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) and the University of Warwick. Keep up with the latest conference news on Twitter.

About the Royal Astronomical Society

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS), founded in 1820, encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science. The RAS organises scientific meetings, publishes international research and review journals, recognises outstanding achievements by the award of medals and prizes, maintains an extensive library, supports education through grants and outreach activities and represents UK astronomy nationally and internationally. Its more than 4,000 members (Fellows), a third based overseas, include scientific researchers in universities, observatories and laboratories as well as historians of astronomy and others.

Follow the RAS on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube. Listen and subscribe to the Supermassive Podcast here.

About the Science and Technology Facilities Council

The Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) is part of UK Research and Innovation – the UK body which works in partnership with universities, research organisations, businesses, charities, and government to create the best possible environment for research and innovation to flourish. STFC funds and supports research in particle and nuclear physics, astronomy, gravitational research and astrophysics, and space science and also operates a network of five national laboratories, including the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory and the Daresbury Laboratory, as well as supporting UK research at a number of international research facilities including CERN, FERMILAB, the ESO telescopes in Chile and many more.

STFC's Astronomy and Space Science programme provides support for a wide range of facilities, research groups and individuals in order to investigate some of the highest priority questions in astrophysics, cosmology and solar system science. STFC's astronomy and space science programme is delivered through grant funding for research activities, and also through support of technical activities at STFC's UK Astronomy Technology Centre and RAL Space at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory. STFC also supports UK astronomy through the international European Southern Observatory and the Square Kilometre Array Organisation.

Visit https://stfc.ukri.org/ for more information.

Follow STFC on Twitter.

About the University of Warwick

The University of Warwick is one of the world’s leading research institutions, ranked in the UK’s top 10 and world top 80 universities. Since its foundation in 1965 Warwick has established a reputation of scientific excellence, through the Faculty of Science, Engineering and Medicine (which includes WMG and the Warwick Medical School).