In new research led by the University of Warwick, scientists have determined the best candidate remnant stars to search for relics of planets, based upon the likelihood of the stars hosting surviving planetary cores and the strength of the radio signal that we can tune in to.

Published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, the research, led by Dr Dimitri Veras from the University of Warwick’s Department of Physics, assesses the survivability of planets that orbit white dwarfs, stars which have burnt all of their fuel and shed their outer layers, destroying nearby objects and removing the outer layers of planets. They have determined that the cores which result from this destruction may be detectable and could survive for long enough to be found from Earth.

The first exoplanet confirmed to exist was discovered orbiting a pulsar by co-author Professor Alexander Wolszczan from Pennsylvania State University in the 1990s, using a method that detects radio waves emitted from the star. The researchers plan to observe white dwarfs in a similar part of the electromagnetic spectrum in the hope of achieving another breakthrough.

The magnetic field between a white dwarf and an orbiting planetary core can form a unipolar inductor circuit, with the core acting as a conductor due to its metallic constituents. Radiation from that circuit is emitted as radio waves which can then be detected by radio telescopes on Earth. The effect can also be detected from Jupiter and its moon Io, which form a circuit of their own.

However, the scientists needed to determine how long those cores can survive after being stripped of their outer layers. Their modelling revealed that in a number of cases, planetary cores can survive for over 100 million years and as long as a billion years.

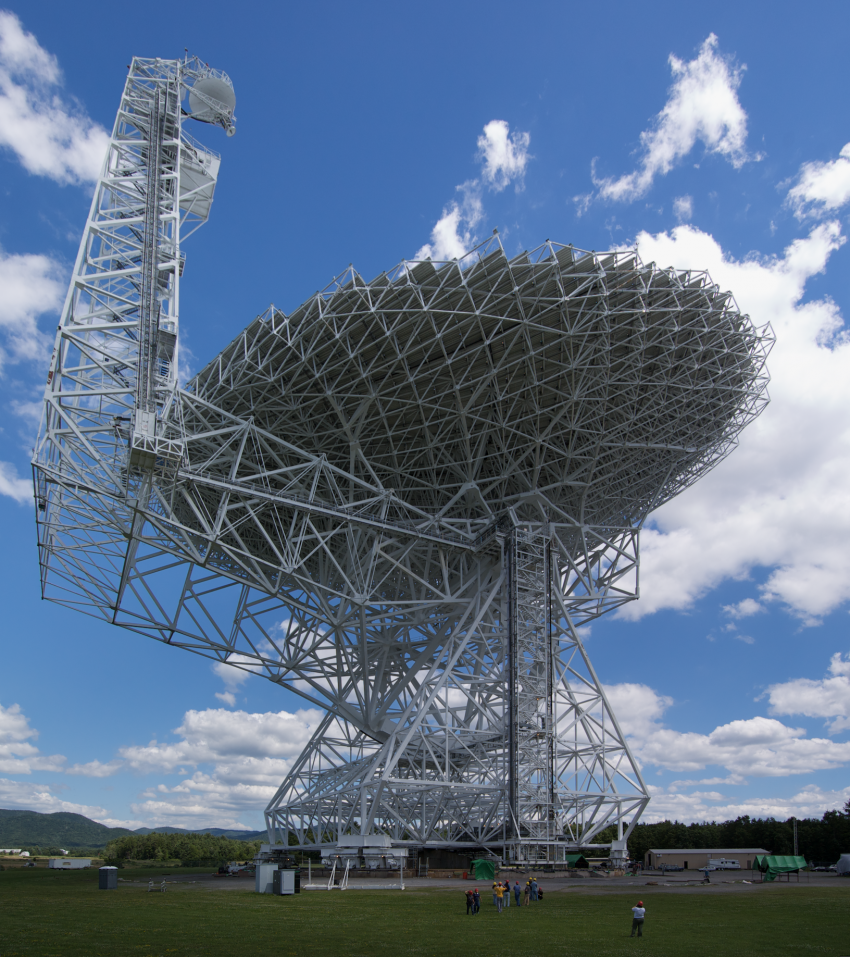

The astronomers plan to use the results in proposals for observation time on telescopes such as Arecibo in Puerto Rico and the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia to try to find planetary cores around white dwarfs.

Dr Veras said: “There is a sweet spot for detecting these planetary cores: a core too close to the white dwarf would be destroyed by tidal forces, and a core too far away would not be detectable. Also, if the magnetic field is too strong, it would push the core into the white dwarf, destroying it. Hence, we should only look for planets around those white dwarfs with weaker magnetic fields at a separation between about 3 solar radii and the Mercury-Sun distance.

“Nobody has ever found just the bare core of a major planet before, nor a major planet only through monitoring magnetic signatures, nor a major planet around a white dwarf. Therefore, a discovery here would represent ‘firsts’ in three different senses for planetary systems.”

Professor Wolszczan commented: “We will use the results of this work as guidelines for designs of radio searches for planetary cores around white dwarfs. Given the existing evidence for a presence of planetary debris around many of them, we think that our chances for exciting discoveries are quite good.”

Dr Veras added: “A discovery would also help reveal the history of these star systems, because for a core to have reached that stage it would have been violently stripped of its atmosphere and mantle at some point and then thrown towards the white dwarf. Such a core might also provide a glimpse into our own distant future, and how the solar system will eventually evolve.”

Media contacts

Peter Thorley

Media Relations Manager (Warwick Medical School and Department of Physics) | Press & Media Relations | University of Warwick

Tel: +44 (0)24 761 50868

Mob: +44 (0) 7824 540863

Robert Massey

Royal Astronomical Society

Tel: +44 (0)20 7292 3979

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877699

Morgan Hollis

Royal Astronomical Society

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877700

Science contacts

Dr Dimitri Veras

University of Warwick

Further information

The new work appears in: “Survivability of radio-loud planetary cores orbiting white dwarfs”, D. Veras and A. Wolszczan, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 488, Issue 1, September 2019, Pages 153–163, Oxford University Press.

Notes for editors

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS), founded in 1820, encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science. The RAS organises scientific meetings, publishes international research and review journals, recognises outstanding achievements by the award of medals and prizes, maintains an extensive library, supports education through grants and outreach activities and represents UK astronomy nationally and internationally. Its more than 4,000 members (Fellows), a third based overseas, include scientific researchers in universities, observatories and laboratories as well as historians of astronomy and others.

The RAS accepts papers for its journals based on the principle of peer review, in which fellow experts on the editorial boards accept the paper as worth considering. The Society issues press releases based on a similar principle, but the organisations and scientists concerned have overall responsibility for their content.