Our solar system and everything within it - including the Earth - will look very different when the Sun dies.

But whether the planet we call home is “swallowed” up by our dying star or manages to escape its clutches, only time will tell.

The inner planets Mercury and Venus will almost certainly be crushed and engulfed by the Sun, according to a new paper published today in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS).

But even if Earth does outlive its star, unfortunately it still wouldn’t be habitable. On the plus side, it would at least fare better than some of Jupiter’s moons, which an international team of astrophysicists say could be dislodged and shredded as the Sun runs out of energy.

They came up with the terrifying prophecy of what our solar system may look like five billion years from now after studying what happens to planetary systems like our own when their host stars become white dwarfs.

“Whether or not the Earth can just move out fast enough before the Sun can catch up and burn it is not clear, but [if it does] the Earth would [still] lose its atmosphere and ocean and not be a very nice place to live,” explained Professor Boris Gaensicke, of the University of Warwick.

If our planet was engulfed by the Sun, along with Venus and Mercury, this would leave Mars and the four gas giants - Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune - orbiting what would ultimately be a white dwarf.

Surviving asteroids and smaller moons would then likely be ripped apart and ground to dust before falling into the dead star, the team of researchers said.

Currently the Sun is burning hydrogen at its core, but once this is used up it will expand and become a red giant, before ending up as a white dwarf – the end state of stars when they have burned all their fuel.

Studying white dwarfs is useful because it offers an insight into different aspects of star formation and evolution.

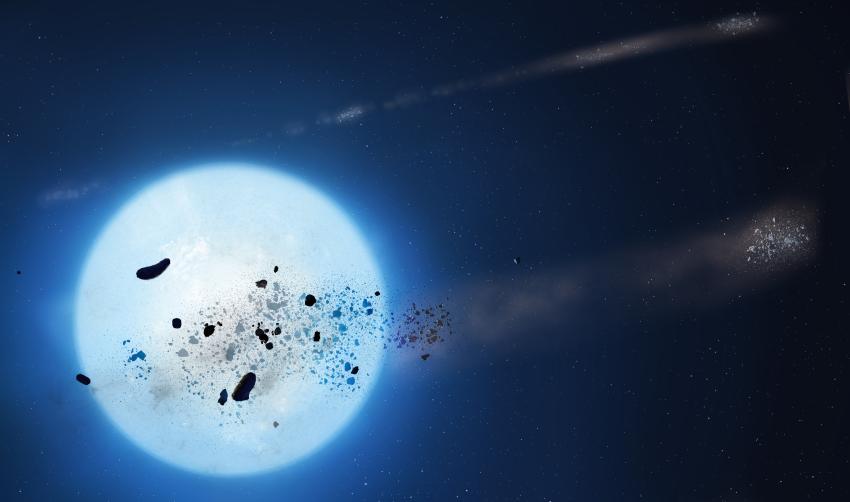

Researchers in this study wanted to know what happens to asteroids, moons and planets that pass close to white dwarfs.

What they found is that the fate of these bodies is likely to be extremely violent and catastrophic. They came to this conclusion after analysing the bodies’ transits – dips in the brightness of stars caused by objects passing in front of them.

Unlike the predictable transits caused by orbiting planets around stars, transits caused by debris are oddly shaped, chaotic and disorderly.

Lead researcher Dr Amornrat Aungwerojwit, of Naresuan University in Thailand, said: “Previous research had shown that when asteroids, moons and planets get close to white dwarfs, the huge gravity of these stars rips these small planetary bodies into smaller and smaller pieces.”

Collisions between these pieces eventually grind them to dust, which then falls into the white dwarf, enabling researchers to determine what type of material the original planetary bodies were made from.

In this new research, scientists analysed changes in the brightness of stars for 17 years, shedding insight into how these bodies are disrupted. They focused on three different white dwarfs which all behaved very differently.

Professor Gaensicke said: “The simple fact that we can detect the debris of asteroids, maybe moons or even planets whizzing around a white dwarf every couple of hours is quite mind-blowing, but our study shows that the behaviour of these systems can evolve rapidly, in a matter of a few years.

“While we think we are on the right path in our studies, the fate of these systems is far more complex than we could have ever imagined.”

The first white dwarf (ZTF J0328−1219) studied appeared steady and “well behaved” over the last few years, but the authors found evidence for a major catastrophic event around 2010.

Another star (ZTF J0923+4236) was shown to dim irregularly every couple of months, and shows chaotic variability on time scales of minutes during these fainter states, before brightening again.

The third white dwarf analysed (WD 1145+017), had been shown by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 2015 to behave close to theoretical predictions, with vast variations in numbers, shapes and depths of transits.

Surprisingly, the transits studied in this research are now gone.

“The system is, overall, very gently getting brighter, as the dust produced by catastrophic collisions around 2015 disperses”, said Professor Gaensicke.

“The unpredictable nature of these transits can drive astronomers crazy – one minute they are there, the next they are gone. And this points to the chaotic environment they are in.”

When asked about the fate of our own solar system, Professor Gaensicke, said: “The sad news is that the Earth will probably just be swallowed up by an expanding Sun, before it becomes a white dwarf.

“For the rest of the solar system, some of the asteroids located between Mars and Jupiter, and maybe some of the moons of Jupiter may get dislodged and travel close enough to the eventual white dwarf to undergo the shredding process we have investigated.”

The paper 'Long-term variability in debris transiting white dwarfs' has been published today in MNRAS.

Media contacts

Sam Tonkin

Royal Astronomical Society

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877700

Robert Massey

Royal Astronomical Society

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877699

Annie Slinn

University of Warwick

Mob: +44 (0)7392 125 605

Science contacts

Professor Boris Gaensicke

University of Warwick

Tel: +60 18 204 3100

Dr Sukuny Ross

Naresuan University

Images and captions

Caption: Clumps of debris from a disrupted planetesimal are irregularly spaced on an long and eccentric orbit around the white dwarf. Individual clouds of rubble intermittently pass in front of the white dwarf, blocking some of its light. Because of the various sizes of the fragments in these clumps, the brightness of the white dwarf flickers in a chaotic way.

Credit: Dr Mark Garlick/The University of Warwick

Further information

The new study 'Long-term variability in debris transiting white dwarfs', Amornrat Aungwerojwit et al., has been published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Notes for editors

About the Royal Astronomical Society

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS), founded in 1820, encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science. The RAS organises scientific meetings, publishes international research and review journals, recognises outstanding achievements by the award of medals and prizes, maintains an extensive library, supports education through grants and outreach activities and represents UK astronomy nationally and internationally. Its more than 4,000 members (Fellows), a third based overseas, include scientific researchers in universities, observatories and laboratories as well as historians of astronomy and others.

The RAS accepts papers for its journals based on the principle of peer review, in which fellow experts on the editorial boards accept the paper as worth considering. The Society issues press releases based on a similar principle, but the organisations and scientists concerned have overall responsibility for their content.