Researchers from Keele University have worked with an international team of astronomers to find for the first time that a white dwarf and a brown dwarf collided in a ‘blaze of glory’ that was witnessed on Earth in 1670. The research is published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, the international team of astronomers, including workers from the Universities of Keele, Manchester, South Wales, Arizona State, Minnesota, Ohio State, Warmia & Mazury, and the South African Astronomical Observatory, found evidence that a white dwarf (the remains of a star like the Sun at the end of its life) and a brown dwarf (a ‘failed’ star without sufficient mass to sustain thermonuclear fusion) collided in a short-lived blaze of glory that was witnessed on Earth in 1670 as Nova Cygni – ‘a new star below the head of the Swan.’

In July of 1670, observers on Earth witnessed a ‘new star’, or nova, in the constellation Cygnus - the Swan. Where previously there was no obvious star, there abruptly appeared a star as bright as those in the Plough, that gradually faded, reappeared, and finally disappeared from view.

Modern astronomers studying the remains of this cosmic event initially thought it was triggered by the merging of two main-sequence stars – stars on the same evolutionary path as our Sun. This so-called ‘new star’ was long referred to as ‘Nova Vulpeculae 1670’, and later became known as CK Vulpeculae.

However, we now know that CK Vulpeculae was not what we would today describe as a ‘nova’, but is in fact the merger of two stars - a white dwarf and a brown dwarf.

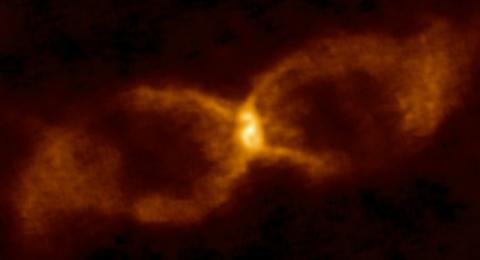

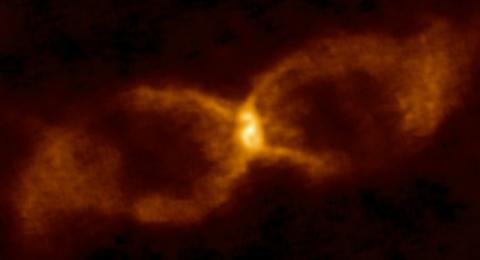

By studying the debris from this explosion - which takes the form of dual rings of dust and gas, resembling an hourglass with a compact central object - the research team concluded that a brown dwarf, a so-called failed star without the mass to sustain nuclear fusion, had merged with a white dwarf.

Prof. Nye Evans, Professor of Astrophysics at Keele University and co-author on the paper explains:

“CK Vulpeculae has in the past been regarded as the oldest ‘old nova’. However, the observations of CK Vulpeculae I have made over the years, using telescopes on the ground and in space, convinced me more and more that this was no nova. Everyone knew what it wasn't - but nobody knew what it was! But a stellar merger of some sort seemed the best bet. With our ALMA observations of the exquisite dusty hourglass and the warped disc, plus the presence of lithium and peculiar isotope abundances, the jig-saw all fitted together: in 1670 a brown dwarf star was ‘shredded’ and dumped on the surface of a white dwarf star, leading to the 1670 eruption and the hourglass we see today.”

The team of European, American and South African astronomers used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array to examine the remains of the merger, with some interesting findings. By studying the light from two, more distant, stars as they shine through the dusty remains of the merger, the researchers were able to detect the tell-tale signature of the element lithium, which is easily destroyed in stellar interiors.

Dr Stewart Eyres, Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Computing, Engineering and Science at the University of South Wales and lead author on the paper explains:

“The material in the hourglass contains the element lithium, normally easily destroyed in stellar interiors. The presence of lithium, together with unusual isotopic ratios of the elements C, N, O, indicate that an (astronomically!) small amount of material, in the form of a brown dwarf star, crashed onto the surface of a white dwarf in 1670, leading to thermonuclear ‘burning’, an eruption that led to the brightening seen by the Carthusian monk Anthelme and the astronomer Hevelius, and in the hourglass we see today.”

Prof. Albert Zijlstra, from The University of Manchester’s School of Physics & Astronomy, co-author of the study, says:

“Stellar collisions are the most violent events in the Universe. Most attention is given to collisions between neutrons stars, between two white dwarfs – which can give a supernova – and star-planet collisions.

"But it is very rare to actually see a collision, and where we believe one occurred, it is difficult to know what kind of stars collided. The type we believe that happened here is a new one, not previously considered or ever seen before. This is an extremely exciting discovery.”

Prof. Sumner Starrfield, Regents' Professor of Astrophysics at Arizona State University comments:

“The white dwarf would have been about 10 times more massive than the brown dwarf, so as the brown dwarf spiralled into the white dwarf it would have been ripped apart by the intense tidal forces exerted by the white dwarf. When these two objects collided, they spilled out a cocktail of molecules and unusual element isotopes.

“These organic molecules, which we could not only detect with ALMA, but also measure how they were expanding into the surrounding environment, provide compelling evidence of the true origin of this blast. This is the first time such an event has been conclusively identified.

“Intriguingly, the hourglass is also rich in organic molecules such as formaldehyde (H2CO), methanol (CH3OH) and methanamide (NH2CHO). These molecules would not survive in an environment undergoing nuclear fusion and must have been produced in the debris from the explosion. This lends further support to the conclusion that a brown dwarf met its demise in a star-on-star collision with a white dwarf.”

Since most star systems in the Milky Way are binary, stellar collisions are not that rare, the astronomers note.

Prof. Starrfield adds:

“Such collisions are probably not rare and this material will eventually become part of a new planetary system, implying that they may already contain the building-blocks of organic molecules as they are forming.”

Media contacts

Sam Lesniak

PR & Communications Manager

Keele University

Tel: +44 (0)1782 733 857

Mob: +44 (0)7825 609 437

Dr Robert Massey

Royal Astronomical Society

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877 699

Dr Morgan Hollis

Royal Astronomical Society

Tel: +44 (0)20 7292 3977 x118

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877 700

Science contacts

Prof. Nye Evans

Keele University

Dr Stewart Eyres

University of South Wales

stewart.eyres@southwales.ac.uk

Prof. Albert Zijlstra

University of Manchester

Image and caption

ESO Picture of the Week: Through the Hourglass

This object is possibly the oldest of its kind ever catalogued: the hourglass-shaped remnant named CK Vulpeculae. Originally thought to be a nova, classifying this unusually shaped object correctly has proven challenging over the years. A number of possible explanations for its origins have been considered and discarded. It is now thought to be the result of two stars colliding — although there is still debate about what type of stars they were.

CK Vulpeculae was first spotted on 20 June 1670 by French monk and astronomer Père Dom Anthelme. When it first appeared it was easily visible with the naked eye; over the subsequent two years the flare varied in brightness and disappeared and reappeared twice, before finally vanishing from view for good.

During the twentieth century, astronomers came to understand that most novae could be explained by the runaway explosive behaviour and interactions between two close stars in a binary system. The features seen around CK Vulpeculae didn’t seem to fit this model particularly well, however, puzzling astronomers for many years.

The central part of the remnant has now been studied in detail using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). This striking image shows the best view of the object to date, and traces the cosmic dust and emission within and around CK Vulpeculae to reveal its intricate structure. CK Vulpeculae harbours a warped dusty disc at its centre and gaseous jets which indicate some central system propelling material outwards. These new observations are the first to bring this system into focus, suggesting a solution to a 348 year-old mystery.

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO) / S.P.S. Eyres

Further information

The new work appears in: “ALMA reveals the aftermath of a white dwarf–brown dwarf merger in CK Vulpeculae”, S.P.S. Eyres, A. Evans, A. Zijlstra, et al., Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (2018), in press (DOI: 10.1093/mnras/sty2554).

A copy of the paper is available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/sty2554

Notes for editors

About Keele University:

- Keele is ranked No. 1 in England for Student Satisfaction in the National Student Survey 2018 (of broad-based universities)

- Keele was awarded Gold in the Teaching Excellence Framework

- 97% of the University’s research was deemed to be world-leading, or of international importance, in the most recent Research Excellence Framework

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS, www.ras.ac.uk), founded in 1820, encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science. The RAS organizes scientific meetings, publishes international research and review journals, recognizes outstanding achievements by the award of medals and prizes, maintains an extensive library, supports education through grants and outreach activities and represents UK astronomy nationally and internationally. Its more than 4,000 members (Fellows), a third based overseas, include scientific researchers in universities, observatories and laboratories as well as historians of astronomy and others.

The RAS accepts papers for its journals based on the principle of peer review, in which fellow experts on the editorial boards accept the paper as worth considering. The Society issues press releases based on a similar principle, but the organisations and scientists concerned have overall responsibility for their content.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/royalastrosoc

Facebook: https://facebook.com/royalastrosoc

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/royalastrosoc/

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/user/RoyalAstroSoc/feed