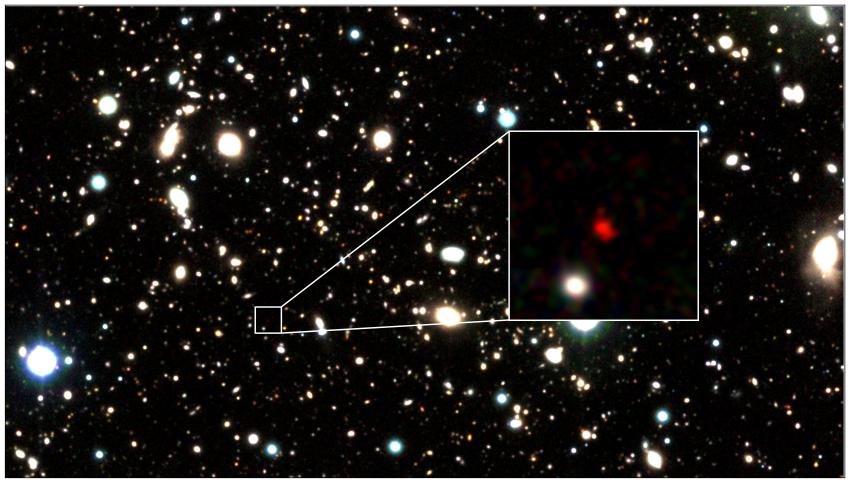

An international team of astronomers, including researchers at the Harvard & Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics, has spotted the most distant astronomical object ever: a galaxy 13.5 billion light years away.

Named HD1, the galaxy is described today in the Astrophysical Journal. In an accompanying paper published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters, scientists have begun to speculate exactly what it is. Shining only ~300 million years after the Big Bang, it may be home to the oldest stars in the universe, or a supermassive black hole.

HD1 was discovered after more than 1,200 hours of observing time with the Subaru Telescope, VISTA Telescope, UK Infrared Telescope and Spitzer Space Telescope. The team then conducted follow-up observations using the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (ALMA) to confirm the distance, which is 100 million light years further than GN-z11, the current record-holder for the furthest galaxy.

The team proposes two ideas: HD1 may be forming stars at an astounding rate and is possibly even home to the universe’s very first stars, known as Population III stars — which, until now, have never been observed. Alternatively, HD1 may contain a supermassive black hole about 100 million times the mass of our Sun.

HD1 is extremely bright in ultraviolet light. To explain this, the team have assumed that some energetic processes are occurring there or, better yet, did occur some billions of years ago.

At first, the researchers assumed HD1 was a standard starburst galaxy, a galaxy that is creating stars at a high rate, however HD1 was estimated to be forming more than 100 stars every single year, a rate at least 10 times higher than what is expected for galaxies of this type.

That’s when the team began suspecting that HD1 might not be forming normal, everyday stars. A supermassive black hole, however, could also explain the extreme luminosity of HD1. As it gobbles down enormous amounts of gas, high energy photons may be emitted by the region around the black hole. In this scenario, it would be by far the earliest supermassive black hole known to humankind, observed much closer in time to the Big Bang compared to the current record-holder.

“The very first population of stars that formed in the universe were more massive, more luminous and hotter than modern stars,” says Fabio Pacucci, lead author of the MNRAS study, and an astronomer at the Centre for Astrophysics. “If we assume the stars produced in HD1 are these first, or Population III, stars, then its properties could be explained more easily. In fact, Population III stars are capable of producing more UV light than normal stars, which could clarify the extreme ultraviolet luminosity of HD1.”

Pacucci adds, “Answering questions about the nature of a source so far away can be challenging. It’s like guessing the nationality of a ship from the flag it flies, while being faraway ashore, with the vessel in the middle of a gale and dense fog. One can maybe see some colours and shapes of the flag, but not in their entirety. It’s ultimately a long game of analysis and exclusion of implausible scenarios.”

“It was very hard work to find HD1 out of more than 700,000 objects,” says Yuichi Harikane, an astronomer at the University of Tokyo who discovered the galaxy. “HD1's red colour matched the expected characteristics of a galaxy 13.5 billion light-years away surprisingly well, giving me goosebumps when I found it.”

“Forming a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, a black hole in HD1 must have grown out of a massive seed at an unprecedented rate,” says Avi Loeb, an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics and co-author on the MNRAS study. “Once again, nature appears to be more imaginative than we are.”

Using the James Webb Space Telescope, the research team will soon once again observe HD1 to verify its distance from Earth. If current calculations are right, HD1 will be the most distant — and oldest — galaxy ever recorded. The same observations will allow the team to dig deeper into HD1’s identity and confirm if one of their theories is correct.

Media Contacts

Gurjeet Kahlon

Royal Astronomical Society

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877 700

press@ras.ac.uk

Dr Robert Massey

Royal Astronomical Society

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877699

press@ras.ac.uk

Science Contacts

Fabio Pacucci

Centre for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian

fabio.pacucci@cfa.harvard.edu

Yuichi Harikane

University of Tokyo

hari@icrr.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Notes for Editors

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS), founded in 1820, encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science. The RAS organises scientific meetings, publishes international research and review journals, recognises outstanding achievements by the award of medals and prizes, maintains an extensive library, supports education through grants and outreach activities and represents UK astronomy nationally and internationally. Its more than 4,000 members (Fellows), a third based overseas, include scientific researchers in universities, observatories and laboratories as well as historians of astronomy and others.

The RAS accepts papers for its journals based on the principle of peer review, in which fellow experts on the editorial boards accept the paper as worth considering. The Society issues press releases based on a similar principle, but the organisations and scientists concerned have overall responsibility for their content.

Keep up with the RAS on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube.