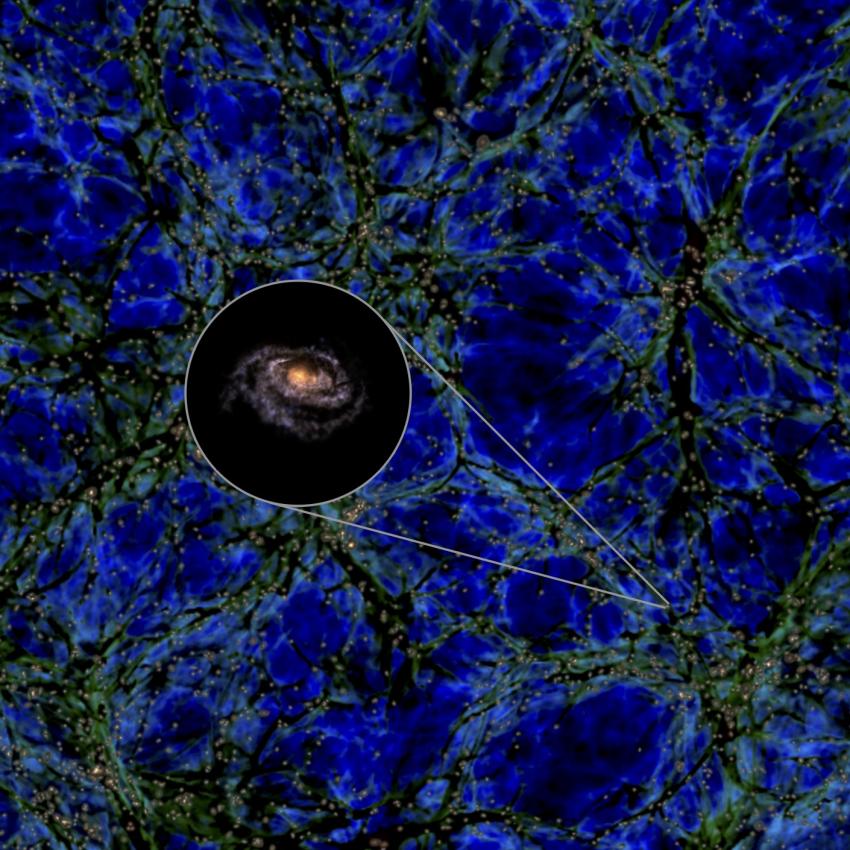

Is the Milky Way special, or, at least, is it in a special place in the Universe? An international team of astronomers has found that the answer to that question is yes, in a way not previously appreciated. A new study shows that the Milky Way is too big for its “cosmological wall”, something yet to be seen in other galaxies. The new research is published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

A cosmological wall is a flattened arrangement of galaxies found surrounding other galaxies, characterised by particularly empty regions called ‘voids’ on either side of it. These voids seem to squash the galaxies together into a pancake-like shape to make the flattened arrangement. This wall environment, in this case called the Local Sheet, influences how The Milky Way and nearby galaxies rotate around their axes, in a more organised way than if we were in a random place in the Universe, without a wall.

Typically, galaxies tend to be significantly smaller than this so-called wall. The Milky Way is found to be surprisingly massive in comparison to its cosmological wall, a rare cosmic occurrence.

The new findings are based on a state-of-the-art computer simulation, part of the IllustrisTNG project, which simulated a volume of the Universe nearly a billion light-years across that contains millions of galaxies. Only a handful – about a millionth of all the galaxies in the simulation – were as “special” as the Milky Way, i.e. both embedded in a cosmological wall like the Local Sheet, and as massive as our home galaxy.

According to the team, it may be necessary to take into account the special environment around the Milky Way when running simulations, to avoid a so-called “Copernican bias” in making scientific inference from the galaxies around us. This bias, describing the successive removal of our special status in the nearly 500 years since Copernicus demoted the Earth from being at the centre of the cosmos, would come from assuming that we reside in a completely average place in the Universe. To simulate observations, astronomers sometimes assume that any point in a simulation such as IllustrisTNG is as good as any, but the team’s findings indicate that it may be important to use precise locations to make such measurements.

“So, the Milky Way is, in a way, special,” said research lead Miguel Aragón. “The Earth is very obviously special, the only home of life that we know. But it’s not the centre of the Universe, or even the Solar System. And the Sun is just an ordinary star among billions in the Milky Way. Even our galaxy seemed to be just another spiral galaxy among billions of others in the observable Universe.”

“The Milky Way doesn’t have a particularly special mass, or type. There are lots of spiral galaxies that look roughly like it,” Joe Silk, another of the researchers, said. “But it is rare if you take into account its surroundings. If you could see the nearest dozen or so large galaxies easily in the sky, you would see that they all nearly lie on a ring, embedded inthe Local Sheet. That’s a little bit special in itself. What we newly found is that other walls of galaxies in the Universe like the Local Sheet very seldom seem to have a galaxy inside them that’s as massive as the Milky Way.”

“You might have to travel a half a billion light years from the Milky Way, past many, many galaxies, to find another cosmological wall with a galaxy like ours,” Aragón said. He adds, “That’s a couple of hundred times farther away than the nearest large galaxy around us, Andromeda.”

“You do have to be careful, though, choosing properties that qualify as ‘special,’” Dr Mark Neyrinck, another member of the team, said. “If we added a ridiculously restrictive condition on a galaxy, such as that it must contain the paper we wrote about this, we would certainly be the only galaxy in the observable Universe like that. But we think this ‘too big for its wall’ property is physically meaningful and observationally relevant enough to call out as really being special.”

Media contacts

Gurjeet Kahlon

Royal Astronomical Society

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877700

press@ras.ac.uk

Dr Robert Massey

Royal Astronomical Society

Mob: +44 (0)7802 877699

press@ras.ac.uk

Science contacts

Professor Miguel Aragón

UNAM

maragon@astro.unam.mx

Dr Mark Neyrinck

Ikerbasque Foundation

mark.neyrinck@gmail.com

Further information

The research appears in ‘The Unusual Milky Way-Local Sheet System: Implications for Spin Strength and Alignment’, Aragon-Calvo et al., published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, in press.

You can find high resolution simulation images and an interactive map of the Local Sheet here.

Notes for editors

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS), founded in 1820, encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science. The RAS organises scientific meetings, publishes international research and review journals, recognises outstanding achievements by the award of medals and prizes, maintains an extensive library, supports education through grants and outreach activities and represents UK astronomy nationally and internationally. Its more than 4,000 members (Fellows), a third based overseas, include scientific researchers in universities, observatories and laboratories as well as historians of astronomy and others.

The RAS accepts papers for its journals based on the principle of peer review, in which fellow experts on the editorial boards accept the paper as worth considering. The Society issues press releases based on a similar principle, but the organisations and scientists concerned have overall responsibility for their content.

Keep up with the RAS on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube.