RAS

RASMeeting the friends

A talk to the friends of the RAS provided an opportunity to chat with interesting – and interested –people.

RAS

RASA talk to the friends of the RAS provided an opportunity to chat with interesting – and interested –people.

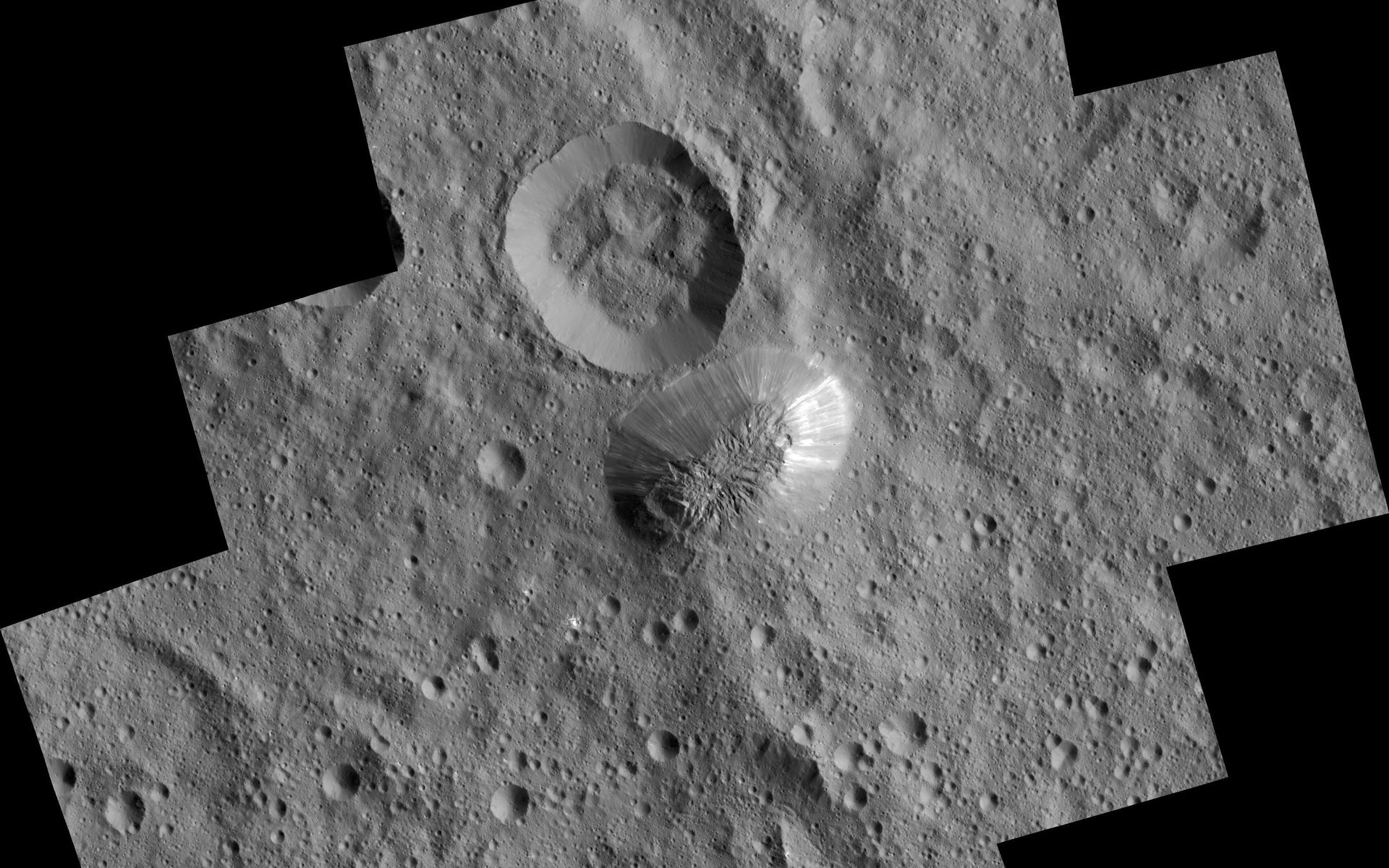

Sodium carbonate flows at Ahuna Mons on Ceres, imaged by the Dawn spacecraft

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-CaltechNASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA

A talk to the friends of the RAS provided an opportunity to chat with interesting – and interested –people.

Last month I had the great pleasure of talking to the Friends of the RAS, on the subject of Volcanoes in Space. This was an opportunity to revist the wonderful discovery by the Voyager spacecraft of active volcanoes on Io, and the rapid changes to the surface of this moon revealed by Galileo and, more recently, New Horizons.

That's not to say I neglected the towering volcanic edifices of Mars; indeed, with Kilauea putting on such a show at the moment, it was interesting to compare the results of volcanoes on the Earth and other planets. The vastly greater size of the martian volcanoes and their calderas is a result of a greater supply of magma and the fact that, without tectonic plates moving across the planet;'s surface, volcanoes on Mars keep growing in place for a lot longer than those on Earth. Lava flows then keep building the typical sheild volcano topography, by effusive volcanism. But the significantly lower atmospheric pressure on Mars means that explosive eruptions are also likely to be a feature of martian volcanism; the pressure drop as magma approaches the surface on Mars is likely to blow the molten rock apart and produce ash, which would foundation over a wider area in the lower gravitational pull. While much of the debris from explosive eruptions in the past is probably blowing around the martian surface and forming dunes, some deposits remain in situ, notably the pyroclastic deposits of Medusae Fossae, which dwarf in volume anything on Earth.

Venus too has volcanoes, some producing extremely long lava flows – the width of the continental US. The heat at the surface of Venus – enough to melt lead – is a contributing factor. Venus, in fact, has huge volcanoes and tiny volcanoes, and everything in between. It even has broad, flat domes that look at if they are built from highly viscous lava. On Earth, viscous lavas arise when magma sits beneath the crust and becomes more silica-rich as a result of fractional crystallisation. They erupt explosively when pressure builds up enough to blow the magma apart. A thick Venusian lithosphere might have the same effect, but the thick and high pressure Venusian atmosphere prevents any such explosive activity.

But one of the most interesting new areas in planetary exploration is the behaviour of the icy moons of Saturn and Jupiter, and the icy dwarf planets. Many of these outer planet moons appear to have subsurface oceans; Enceladus has plumes of water that indicate the existence of volcanoes at depth. This is intriguing given the possible origin of life on earth at hydrothermal vents, regions of the ocean crust where water is heated by recent volcanic activity, and released.

Dwarf planets such as Ceres also show apparent cryovolcanoes, eruptive features that exude forms of ice and relatively low density minerals such as sodium carbonate. These are closer to density driven instabilities such as diapirs on Earth than volcanoes, but they share morphological features and indicate some instability in their home worlds.

It was a real pleasure to be able to spend time discussing these new areas of research with the Friends, in the RAS lecture room and afterwards in the Library. I'm grateful to Marcus Hope for inviting me along, and the the Friends who were present for such a warm and interested welcome.

If you would like to submit an article to A&G Forum then please go here.