On Thursday 10 June, the whole of the UK will see a partial eclipse of the Sun. These are quite rare, and this one will be a significant event. That morning, the Moon will pass right in front of the Sun, blotting out up to 38% of its disc.

However, it is extremely dangerous to just go out and look up. The Sun is so bright that just looking at it can blind you, so you’ll need to prepare beforehand. There are various ways to observe it safely, using both everyday materials and telescopes or binoculars. This guide tells you what will happen and how you can see all the stages of the event.

What will happen

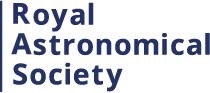

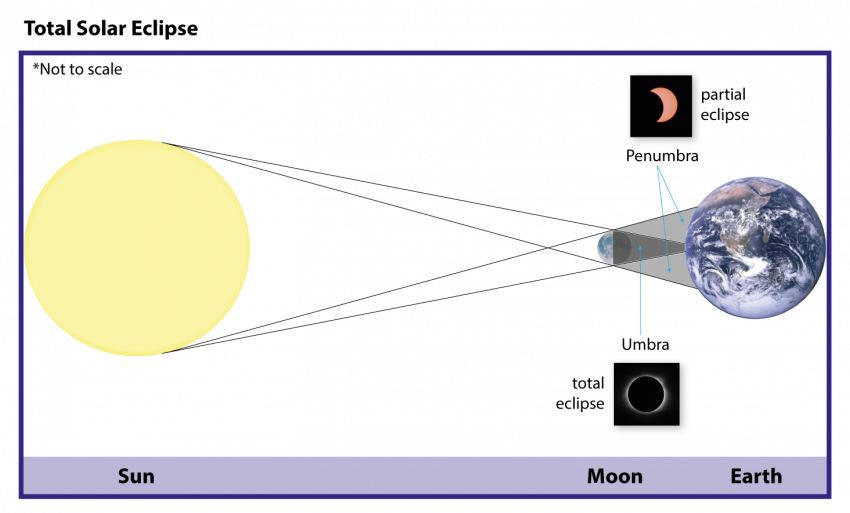

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon comes directly between the Sun and the Earth. Anyone lucky enough to be within a certain area will witness the Moon crossing directly in front of the Sun. On 10 June, people in a very narrow band across the Earth’s surface in Canada and the north polar regions will see the Moon passing centrally in front of the Sun. But on this occasion the Moon’s disc will be slightly smaller than that of the Sun, leaving a bright ring around the lunar silhouette, so it won’t be a total eclipse where everything goes dark. Eclipses like this are called annular after the ring, or annulus, seen at mid-eclipse.

But from the UK, well away from this track, the Earth, Moon and Sun are less precisely aligned. This means that the Moon appears to only take a fairly small bite out of the edge of the Sun’s disc. The eclipse will take place over a couple of hours, with mid-eclipse shortly after 11 am. It’s not as spectacular as the view from the track where the eclipse is annular, but If you take the proper precautions it’s a great thing to watch, and something you’ll remember for the rest of your life.

How to observe

Danger! How NOT to view a solar eclipse: with your eyes! Viewing a solar eclipse is potentially hazardous and should only be attempted with caution. You should never, ever – under any circumstances – look directly at the Sun!

Forget anything you may have heard about using bits of film to look through, even if you can find any old negatives stashed away, or smoked glass. These methods were always dangerous. The Sun is so bright, particularly when high up in June, that suitable filters have to be so dense that you can’t normally see through them. And don’t try black plastic such as bin liners – these may look dense, but they transmit infrared heat, which can seriously damage your eyesight even though the Sun might look dim. And even the darkest sunglasses are completely useless.

Here is an update from Prof. Lucie Green on how to safely view the eclipse using different methods.

Eclipse glasses If you have any official CE-marked eclipse glasses from previous events these may be safe to use, but only if they have been stored safely and the surfaces haven’t been damaged in any way. Check that there are no tiny holes in the coatings, or wrinkles where the coating may have worn away.

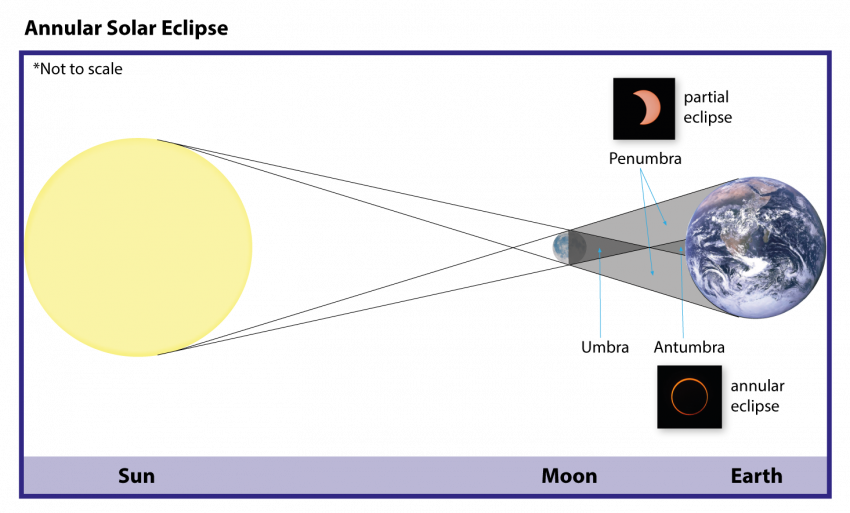

Mirror projection If you don’t have any eclipse glasses, there is a good way to view the progress of the eclipse using nothing more elaborate than a small mirror. A compact or small shaving mirror is ideal, particularly if it has a stand to hold it in position. Use the flat side, not the concave or magnifying side.

All you need to do is to cover the mirror with paper in which you have cut a hole about 4 mm or an eighth of an inch across. It doesn’t have to be neat, or even round. Then shine the Sun’s reflection from the mirror into a room or onto any surface that’s in shade. You’ll see a circular spot of light which is in fact an image of the Sun. A projection distance of about 5 metres (15 feet) works perfectly, giving an image about 50 mm (2 inches) across, and you can view the image on a wall or a white piece of paper or whatever you have to hand.

As the eclipse progresses you’ll see in perfect safety the Moon progressively taking a bite out of the edge of the Sun. It will be a little fuzzy around the edges, but it will be obvious to see.

Other simple methods of projection, such as using a pinhole in the side of a cereal packet, are possible but the image size is very small – only about 1 mm. So the fairly small bite from the Sun will hardly be visible.

Projection using binoculars or telescope. You can use a small telescope or binoculars with great care to project the Sun’s image for a very sharp view. Point the instrument at the Sun, judging from its shadow when it is in line. Hold a sheet of white paper about 30 cm (12 inches) away and you should see a bright spot appear when everything is lined up. You will probably need to focus to get a sharp image.

If you use a tripod make sure that there’s no chance that someone can accidentally look into the eyepiece of the instrument – this is the main danger with this method. The lesser danger is ruining the interior of the eyepiece. If the Sun’s bright image moves out of the field of view it will be focused on the interior of the eyepiece, which these days is often made of plastic even if the barrel is metal. The result will be very obvious damage to the field stop, which is what gives you the well-defined circle when you view a scene. You have been warned!

When to look

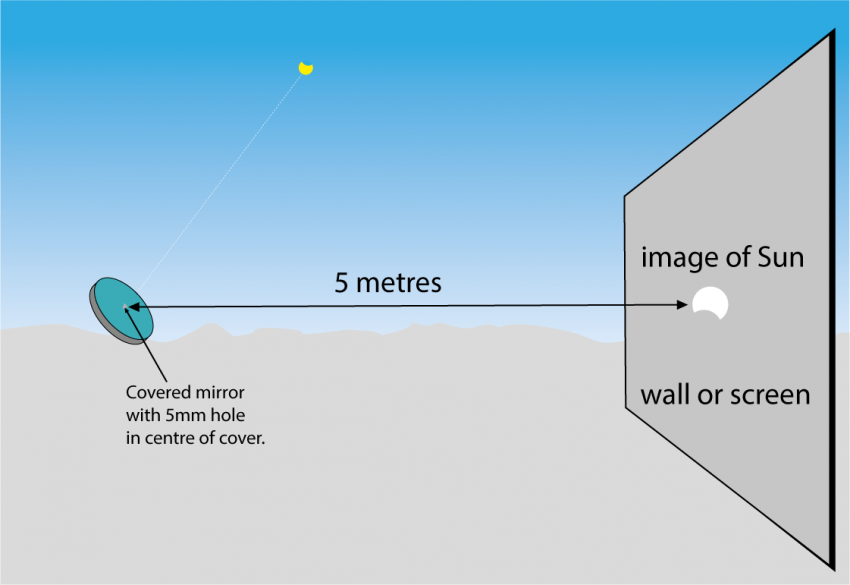

If you live in the UK you will see a partial eclipse with between one and two fifths of the Sun covered by the Moon. The farther north you are located, the more of the Sun will be obscured. If the weather is favourable, at the maximum point of the eclipse the Sun will appear to have a large bite taken out of it.

The precise times of the eclipse and its appearance vary with location. Observers in Lerwick in the Shetland Islands will see the eclipse begin at 1015 BST, mid-eclipse will be at 1127 BST when 38% of the Sun will appear to be covered by the Moon, and the eclipse will end at 1244 BST. In London the eclipse starts at 1008 BST, mid-eclipse is at 1113 BST when 20% of the Sun is obscured by the Moon, and the eclipse ends at 1222 BST.

The eclipse begins with first contact. You can’t see details on the disc of the Moon, or the whole of the disc, during a partial eclipse – all you see is that a bit of the bright Sun is missing. It may take a minute or so before you notice it.

The Moon continues to move ever so slowly across the Sun until after about 70 minutes (on this occasion) it has reached its maximum, and the Sun will appear to be missing a large chunk. The exact timings depend on where you are in the UK. Then the Moon moves off again, and after roughly another 70 minutes it’s all over, with fourth contact.

What happened to second and third contacts? They only apply during a total eclipse, which we won’t see this time. You’ll either have to travel abroad or wait until 2090 to see a total eclipse from the mainland UK.

This year’s event won’t be a total eclipse anywhere, which would give amazing views of the Sun’s outer atmosphere (the corona) and maybe prominences, which look like flames around the edge of the Sun. During totality, the sky goes dark for a few minutes. For us, although between one and two fifths of the solar surface will be covered by the Moon, the sky will only appear slightly darker and most people are unlikely to notice any difference.

If you have a telescope and are projecting the image, or are viewing it using a safe solar filter, you may notice that there are dark spots on the Sun: sunspots. These are places where relatively cool gas, that doesn't glow as brightly as the gas around it, is trapped by strong magnetic fields. Although sunspots look black, they are still part of the Sun and if the Moon’s disc happens to cross one you could notice that the Moon’s disc is darker than the sunspot. At the moment the Sun is not very active, but there are usually small spots visible.

Also look at the edge of the Moon (known as the limb) and you might see that it isn’t completely smooth, as you can see mountains or valleys on the limb silhouetted against the Sun. But you’ll probably see a lot of shimmering at the limb, which is caused by turbulence in our own atmosphere rather than anything astronomical.

For teacher resources or to learn more about eclipses, please take a look at these links:

- Role play a solar eclipse: Years 2 -5

- Solar Eclipse Worksheet: Years 7-9

- The Mathematics of a Total Solar Eclipse: Years 10-11

- Solar Eclipse News Article

The Royal Astronomical Society would like to thank the Society for Popular Astronomy (SPA) and the British Astronomical Association (BAA) for their collaboration on this article.

The Society for Popular Astronomy (SPA) is aimed at beginners in astronomy of all ages through its bimonthly magazine, Popular Astronomy, and helpful website. It encourages observing the sky with the naked eye and simple equipment.

Follow the SPA on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube

The British Astronomical Association (BAA) is aimed primarily at amateur observers, especially the possessors of small telescopes, to help them with all kinds of astronomical observations, to circulate current astronomical information, and to encourage a popular interest in astronomy.

Follow the BAA on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube